The “Christianized” Nansemond of Deep Creek: An Incomplete History

The mid 1600s was a transformational period for the Nansemond people. After a series of violent conflicts between the Powhatan Chiefdom and English colonists, the Nansemond community was divided between those who chose to assimilate to a “Christianized” lifestyle and those who chose to remain “traditional.”1 As Nansemond people were displaced from their ancestral land (along the Nansemond River in present day Suffolk) through encroachment, the “Christianized” Nansemond shifted east toward Norfolk and the “traditional” Nansemond shifted west toward Southampton (and merged with the Nottoway).

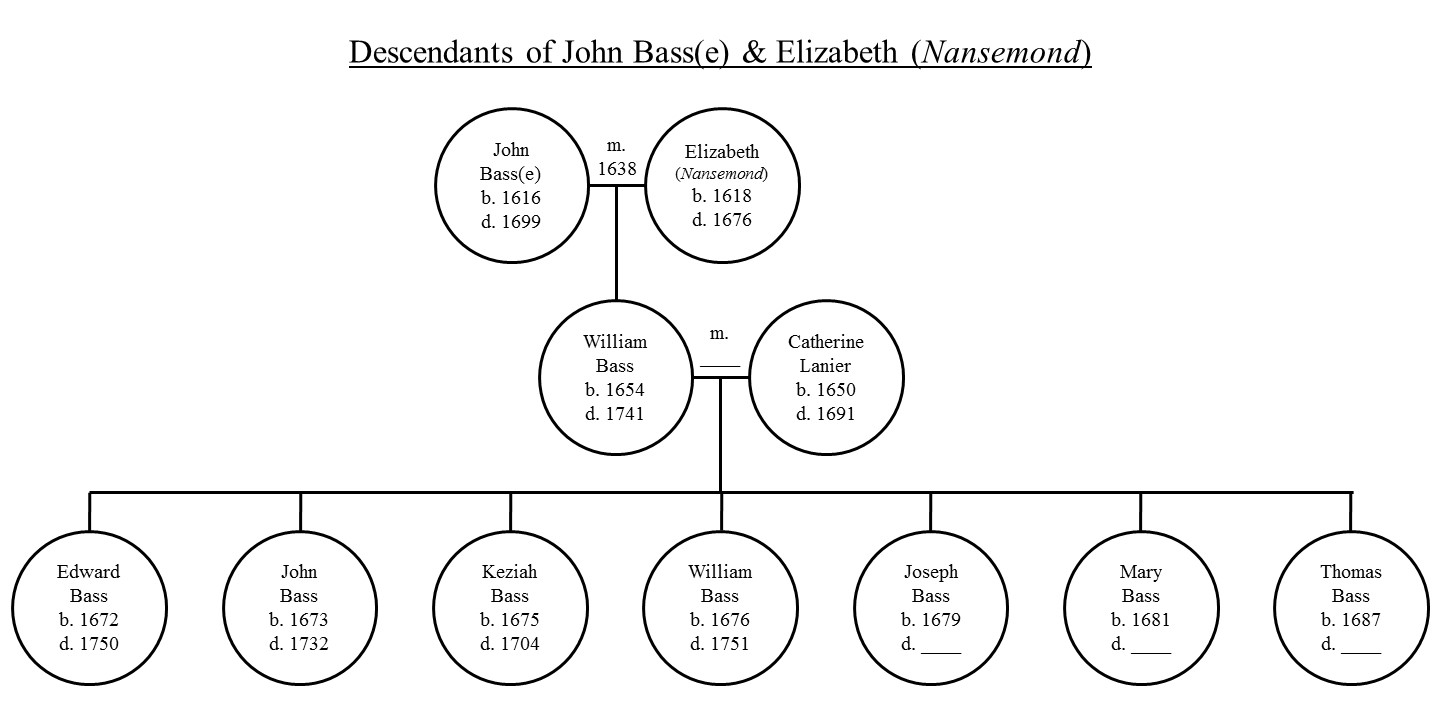

Members of the Nansemond Indian Tribal Association (NITA) descend from the “Christianized” Nansemond who eventually settled in Deep Creek (a proximate reference to Yadkin and Bowers Hill) at the northeastern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp. The ancestral couple at the core of this community was John Bass(e) (b. 1616), an English colonist and minister, and Elizabeth (b. 1618), a “Christianized” Nansemond woman and daughter of a Nansemond Chief. Of their eight children, their son William Bass (b. 1654) has been the focal point of most Nansemond genealogical research.

In my previous article on the NITA, I shared a summary of researchers from inside and outside the tribal community. Despite decades of concentrated research on the “Christianized” Nansemond of Deep Creek, there are still a surprising number of data gaps regarding this group of people. In this article, I will present some Nansemond relationships as they are currently outlined by multiple published researchers and some errors and unanswered questions that have caused confusion.

William Bass (b. 1654) & Catherine Lanier (b. 1650)

The descendants of William Bass (b. 1654) and Catherine Lanier (b. 1650) define a number of prominent Bass lineages. Their two oldest sons, Edward Bass and John Bass, relocated to North Carolina in the early 1700s and have been thoroughly researched by their descendants (see Lars Adams’ Research (John Bass Descendant) and Kianga Lucas’ Research (Edward Bass Descendant)). The rest of William and Catherine’s children remained in Virginia; however, their two daughters, Keziah Bass and Mary Bass, appear to have died unmarried and without children and there is little information about the fate of their son Joseph Bass. Their sons William Bass and Thomas Bass carried the Nansemond legacy forward on ancestral land; however, there is unexplained disparity in their recorded history.

William Bass’ Land In Deep Creek

The earliest reference to William Bass’ (b. 1654) land was made on 17 March 1726 when he appeared before a Norfolk County court to claim rightful possession of cleared swamp lands adjoining the Great Dismal Swamp based on the use of these lands by his Nansemond forebears since before English governance in Virginia (a transcription of this court record is in Bass Families of the South, Page 74). Under the Treaty of 1677, an agreement between Charles II of England and representatives from several Virginia Indian tribes, Indians were entitled use of their ancestral lands for subsistence (fishing and hunting) and to bear arms as long as they were obedient to the English government.

This court record does not contain the detail of a deed so it is unclear exactly where this land was but there are some clues. The area of Deep Creek was documented as an Indian hunting ground and geographically matches the description of the land William Bass referenced in court. Then, on 6 January 1729 William Bass purchased 103 acres in Norfolk County at the mouth of Deep Branch. This may have been the time when William Bass’ family shifted from their residence on the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River (a short distance away) to the Deep Creek community.

William Bass’ family was not the only one with land spanning from the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River to Deep Creek. John Nichols was a neighbor with a manor plantation (500 acres) on the southeastern side of the Western Branch. Nichols also owned land in Deep Creek on the Southern Branch (350 acres originally patented by Richard Batchelor on 15 March 1675) and on the Northwest River (100 acres just north of the North Carolina state line) which he leased. Nichols owned at least one water mill which was a valuable resource of the time.

John Nichols, who was often referred to as Major—an indication that he was a member of a standing militia in the area—married Judith Bowers Spivey (the widow of Matthew Spivey) later in life and it is possible that he had a previous marriage (through which he fathered Sarah Nichols). Prior to marrying Judith, John also appears to have fathered two illegitimate children, John and Sarah, by his slave Jean Lovina. These details can only be inferred (not verified) through the contents of his will (which proved 17 May 1697).

Neighbor Relationships

By the time William Bass bought his 103-acre tract of land in Deep Creek on 6 January 1729, John Nichols, his wife Judith, step-son (and likely son-in-law) Matthew, and mulatto son John were all deceased but his homestead clearly remained. Just a few months after William Bass’ land purchase, on 20 April 1729, William’s son, William (b. 1676), married Sarah Lovina (Nichols’ daughter). A few weeks later, on 2 May 1729, William’s son, Thomas (b. 1687), married Tamer Spivey (Nichols’ granddaughter). This sequence of events presents a strong case that the family of William Bass and Catherine Lanier lived in a neighboring homestead to the family of the deceased John Nichols.

These relationships also suggest that Sarah Lovina and Tamer Spivey were living in the same location when they married Bass men. Despite being manumitted, as an unmarried mulatto woman Sarah Lovina likely would have continued to live and work where she did all her life. Similarly for Tamer2, as an unmarried woman whose parents were deceased, she likely lived with family members.

When William Bass (b. 1676) and Sarah Lovina (b. 1682) married in 1729 they were 53 and 47 years old. This is clearly late for a marriage but may have been advantageous to both parties. William secured a considerable amount of land through his marriage to Sarah (her 250-acre inheritance) and Sarah secured a legal representative to manage her inheritance (which was previously being leased by Daniel Burne).

The Details of John Nichols’ Will

| Heir | Inheritance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Judith (Bowers Spivey) Nichols | Dower interest in the plantation John Nichols was living on (500 acres) and any profits to be gained from land called an Island on the Northwest River in Norfolk County (100 acres). | Dower interest is only for the remainder of the spouse’s life and does not equate ownership. Judith Nichols’ Bowers relatives owned neighboring land. |

| Matthew Spivey | The plantation John Nichols was living on (500 acres) after the death of his mother and shared rights to swamp land (entered by Eleazer Tart) at the head of Nichols’ plantation. | Matthew Spivey married Sarah Nichols (likely the daughter of John Nichols). Matthew died (testate) before his mother leaving her as guardian of his children (suggesting that Sarah may have been deceased). Matthew’s daughter Tamer married Thomas Bass. The Tarts owned land adjoining Nichols and were also neighbors of William Bass (b. 1654, father of Thomas Bass), with Thomas Tart and Enos Tart as witnesses of his 1740 will. |

| Ann Spivey | Land called an Island on the Northwest River in Norfolk County (100 acres) after the death of her mother. This tract of land was purchased from Dan Browne. | Ann Spivey married John Granberry (a neighbor of John Nichols). They sold this tract of land on 13 July 1704 to Moses Prescott. |

| John Lovina | Manumission. 150 acres of land on the Southern Run of a 350-acre tract in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River (now in possession and occupation of Daniel Burne). 160 acres of land in the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River joining the land of the late William Davenell. A water mill at the head of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River which was bought from John Ives and formerly owned by Captain Carver. | John Lovina was apprenticed to Nathan Newby at the time of this will. He later married Anne ________ and had a son, William Lovina. William sold all but 60 acres of his inherited land (presumably the remainder of the Davenell tract) and he was taxed in the home of John Bowers (the cousin of Judith Nichols) in the 1730s. |

| Sarah Lovina | Manumission. 200 acres of land on the Northern Run of a 350-acre tract in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River (now in possession and occupation of Daniel Burne). | Sarah Lovina was a minor at the time of this will and likely continued to live and work for the family. She later married William Bass. Prior to their marriage, William purchased the land adjoining this tract from William Lovina (Sarah’s nephew). |

The details of John Nichols’ will reveal the close interconnectedness of Nichols’ heirs with the family of William Bass and Catherine Lanier. Their actions (e.g., witnessing records, intermarrying, buying and selling land) were common exchanges between neighbors. Their extended families spanned from the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River to Deep Creek which is where the “Christianized” Nansemond community has continued to live for centuries.

Thomas Bass also had two wives. His son, William Bass (b. 1725), was born of his first marriage to Martha Willis. Thomas lived on his father’s property (William Bass (b. 1654)) on the Western Branch at least through the 1730s. While his brother, Willam Bass’ (b. 1676), life was well documented, Thomas Bass’ (b. 1687) life is poorly documented after 1750 and his children migrated in a few different directions.

A Cohesive Family

William Bass (b. 1654) left a will dated 1 October 1740 and died on 13 August 1742. In his will, he left his sons William, Edward, Joseph, and Thomas small bequests (a convention to avoid legal disputes over omission; John and Keziah were left out because they predeceased their father). William left his daughter Mary all of his cash and land if she could save it after his decease. This statement suggested that he may have faced financial and/or legal problems near his death.

The uncertain terms of William’s will beg the question, “Where did his surviving family members live after his death?” What can we learn from subsequent records about familial relationships? The actions of William Bass’ and Thomas Bass’ descendants reveal a number of clues about what happened.

William Bass (b. 1725), the son of Thomas Bass and Martha Willis, was taxed as part of his uncle, William Bass’ (b. 1676), household in 1751. They were recorded within the Southern Branch District from Batcheldor’s Mill to Portsmouth which is precisely where John Nichols’ 350-acre tract left to the Lovina children was located (note that the tract was originally patented by Richard Batchelor). From there, William was taxed in his own household from 1752-1754 (the years immediately following his uncle’s death), and then he was taxed in his aunt’s household, Sarah (Lovina) Bass, from 1756-1757.

William married Naomi Hall some time around 1765 and was taxed on and off with his cousin John Bass (b. 1731), the son of William Bass and Sarah Lovina, through the 1760s. On 17 May 1764, William Bass, his cousin John Bass (and his wife Elizabeth) sold a 50-acre tract of land to Robert Kinder together. John Bass also sold land adjoining Robert Kinder to William Bass’ uncle, Ebenezer Hall, on the same day. Later in 1764, William Bass and John Bass were sued for debt by Solomon Hodges (another sign that they had shared assets).

The descendants of these Nansemond brothers, William Bass (b. 1676) and Thomas Bass (b. 1687), remained connected into subsequent generations. William Bass (b. 1755, the great great grandson of William Bass and Catherine Lanier) gifted 30 acres to Willis Bass (b. ~1763, the great grandson of William Bass and Catherine Lanier). Beyond their shared lineage, these familial gestures more than 100 years later demonstrate that these people were part of the same cohesive Nansemond-descended family.

Several of the children of William Bass and Naomi Hall (i.e., Joseph, Thomas, and William) formed close relationships with their Hall relatives and migrated with them over the North Carolina state line into border communities in Currituck, Camden, and Pasquotank counties. Their son, James, fought in the Revolutionary War and migrated to Tennessee (along with several Hall relatives) to claim bounty land and their son, Willis, was the only to remain in Norfolk county.

The 1830s was another tumultuous time for people of mixed ancestry due to increasing laws and restrictions against individuals of any African ancestry following a number of slave uprisings (most notably Nat Turner’s Rebellion). Court records from the 1830s—representing an external perspective—reveal that descendants of William Bass (b. 1676) were identified as Indian the same as descendants of his brother Thomas Bass (b. 1687). The Bass family bible—representing an internal perspective—also contains the births of both William Bass and Thomas Bass’ descendants (through his grandson Willis Bass and his wife Jemima Nickens).

These records generated inside and outside the Deep Creek Nansemond community demonstrate two important points: 1) the descendants of both William and Thomas Bass identified as Indian and 2) they were part of the same functional family—living together and sharing assets. On a larger scale, these records also reveal that sociopolitical pressures (not tribal necessity) were the primary drivers for the generation of these records.

Errors & Unanswered Questions

Evidence supporting the closeness of William Bass and Catherine Lanier’s children is undeniable. The sole difference between the descendants of their son William and the descendants of their son Thomas is that William’s children repeatedly appeared in court to affirm their Indian ancestry. What could be the cause for this difference in family records? A potential explanation is evident in the research of Helen Rountree.

In Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries, Helen Rountree candidly discussed the fragility of Indian identity in early colonial life. The marriage of a local man (William Bass) to a freed former slave (Sarah Lovina) caused the neighboring English colonists to perceive them and their relatives as mulatto rather than Indian. The confusing thing about Rountree’s statement is that she notes the couple “may not have been ancestral at all” yet they clearly must have been perceived as part of the Nansemond community in order for their marriage to affect the Nansemond reputation as a whole.

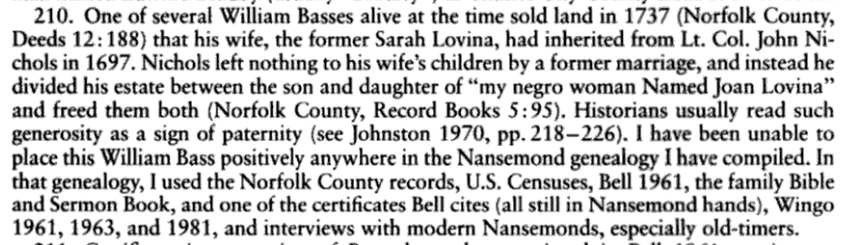

In Rountree’s notes section she made some additional statements about William Bass and Sarah Lovina:

- In 1737 William Bass sold land that his wife, Sarah Lovina, inherited from John Nichols in his 1697 will. (Proven Fact)

- John Nichols left nothing to his wife’s children by a previous marriage. (Proven False)

- John Nichols freed two mulatto children of his slave Joan Lovina and divided his estate between them (suggesting paternity). (Highly Probable)

- This William Bass does not fit into the Nansemond genealogy she compiled. (Highly Improbable)

The inaccuracies in these statements—from the distancing of William Bass and Sarah Lovina from the Nansemond tribal lineage to the complete falsehoods about John Nichol’s will—are surprising. Rountree is the preminent researcher of Virginia Indians and has researched their corresponding communities for decades. One cannot say why Rountree made these statements but a large collection of records present an opposing version of history to hers.

It is possible that sociopolitical pressures around William Bass’ (of English and Nansemond ancestry) marriage to Sarah Lovina (of unspecified mulatto ancestry) forced him to declare his Indian identity more explicitly in order to differentiate himself from mulattoes. Meanwhile, Thomas Bass (also of English and Nansemond ancestry) and his wives, Martha Willis and Tamer Spivey (of presumably English ancestry) may not have encountered the same scrutiny. These efforts to control public perception—a response to external pressures rather than an internal requirement—have had lasting effects on the ongoing effort to document Nansemond ancestry.

Unfortunately, Helen Rountree is not the only researcher who has created confusion surrounding this lineage. Albert Bell, author of Bass Families of the South, also treated the descendants of William Bass and Catherine Lanier differently. Bell abstracted a number of Bass deeds from Norfolk County; however, he placed more importance on certain deeds than others.

Thomas Bass’ deed is listed as a “miscellaneous note” without detail while other deeds are listed with grantee, grantor, and other contextual details. Lack of detail about the land makes it impossible (at least within the context of the book) to trace its connection to other land referenced. Thomas is documented as part Bell’s Nansemond lineage so why was his land sale considered “miscellaneous”?

Paul Heinegg, author of “Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to about 1820” integrated Thomas Bass into Nansemond genealogy but used Bell’s book as a source of deed information. Thomas Bass’ exact location and relationships remain obscure compared to neighboring families and Heinegg’s chronology of William Bass’ life is inconsistent with his narrative (see order of marriage and land purchases). These issues draw the accuracy of the both Bell and Heinegg’s abstracts into question requiring review of the original records.

Incomplete History and Its Consequences

According to the Board for Certification of Genealogists, “reasonably exhaustive research” is a condition of credibility. It means that a researcher must examine a “wide range of high quality sources” to minimize the probability that “undiscovered evidence will overturn a too-hasty conclusion.” Due to missing records, the misinterpretation of records, and the dependence on second-hand research over primary records, it is my opinion that no researcher (including myself) has met this genealogical standard for the “Christianized” Nansemond of Deep Creek.

The current evidence suggests that descendants of Thomas Bass (b. 1687)—the son of William Bass and Catherine Lanier—should be represented within the NITA. The pervasive obscurity on some of these details, along with a number of disagreements related to Nansemond genealogy outside of Virginia, has limited enrollment eligibility within the present tribal association to a very small group with complete, unquestioned lineage.

The legacy of the “Christianized” Nansemond demonstrates the challenges associated with using race- and ethnicity-related data sources (i.e., court records) as a stronger indicator of community cohesion than data sources which directly connect individuals and families (i.e., deeds and wills). The strong evidence needed to include all descendants of William Bass and Thomas Bass in Nansemond tribal lineage has survived but it must be collected from direct sources, thoroughly analyzed, and put into the proper context.

Notes

1Helen Rountree used these terms to distinguish between the two factions. The names of some of the Nansemond who lived with the Nottoway still exist in deeds. The Legislative Petition of 1786 contains a transcript in which the last five Nansemond (Celia Rogers, John Turner, Molly Turner, Simon Turner, and a fifth person who did not sign) requested to sell off the reservation. After the reservation was sold, the remaining Nansemond went to live with the Nottoway.

2Charles McIntosh, author of “Brief Abstracts of Norfolk County Wills, 1710-1753,” misinterpreted the text in the will of Matthew Spivey to read “Thomas” (suggesting a son). The original will as well as the will of Matthew’s mother, Judith Nichols, reveals the correct name to be “Tamer” (a daughter).

Paul Heinegg’s abstracts on the Bass, Hall, and Leviner families have been used as supplemental references throughout this article. Heinegg’s abstracts are living records and are updated intermittently. All references in this article are reflective of his abstracts as of this publication date.

I have an ancestor that married a woman named Eliza Bass in Wake County, NC. My great great great grandmother’s brother Thomas Roe married Eliza Bass in the 1830’s. I have been unable to find the parents of Eliza Bass. Thomas Roe’s in 1850 was brick mason. Both listed as Free Persons of Color.

LikeLike

My name is Brent Stanley. My ancestors I’m having problems with is Moses Bass b.1778 Duplin, N.C. d. 1845 Bass Hammock, Bear Head Creek, Starks, Louisiana. Jeremiah Bass Jr. b.1746 Bertie, N.C d. 1808 Adams County, Mississippi. His father Jeremiah Bass Sr. b.1720/24 Bertie, N.C. , Edward Bass b.1697 Bertie, N.C., John Bass Sr. d.1673 Nansemond, Suffolk, Va. William Bass b. 1654 Isle of Wight, Va. I was wondering if you know anything on this linage. Does it go back to the Nansemond Tribe? Folks call us Redbone & Melungeon of Bear Head Creek, Starks, Louisiana. I moved from Louisiana a while back. I live in Connecticut now and trying to track down my roots. My DNA says Native! My Grandma is Pearl Bass on my Dad’s side. Mom’s side Grandmaw Janie Perkins. We all came from the Carolina’s & Virginia’s & Appalachia. Surnames in my tree of life are Stanley, Bass, Perkins, Gill, Hoosier, Ashworth, Dial / Doyle, Gibson, Terrell, Goodman, Collins, Mullins, etc. Willing too show DNA if it will help. I guess the one drop rule among other thing made us leave. But we found peace in No Man’s Land Spanish Louisiana. Where we are still today!! Any help would be Awesome!! Sincerely Just Another Redbone Looking For Roots!!!

LikeLike

William Basse’s (1654-1741) parents were English immigrant John Basse (1616-1699) and Elizabeth (1618/20-1676), the daughter of Robin Pattanochus, Chief of the Nansemond Nation (1590-1676) and Linda Nansemond Tucker (1595-1676).

From the Basse Family Bible:

“John Basse married ye dafter of ye King of ye Nansemond Nation by name Elizabeth in Holy Baptizm and in Holy Matrimonie ye 14th day of August in ye yeare of Our Blessed Lord 1638…”

LikeLike

Elizabeth Pearl Bass m. To Jesse Leslie Bass, father Gilbert Green Bass?

LikeLike

I was thoroughly engrossed while reading this article. My father’s family was in Tarboro/Edgecombe county, NC. Growing up we were always told that our grandmother was of Native American/Indian descent. What I have found through DNA research is this: My gr grandmother was Emma Bass daughter of Gaston Bass and Lucenda Holloman. Emma married a Jesse M. Whitley and had two children Annie A Whitley and Daniel Whitley. She then married my gr grandfather Atlas Ham(m).

My records indicate that Gaston was the son of James Bass and Celia Godwin and I believe that James Bass’ parents were Absolom Bass and Dorcis Langley. My gedmathch is MX6250243. Please help if you can.

LikeLike

Hi! I am directly related to the Leviners and to Jean Lovina. They will still to this day claim native American ancestry but my DNA says otherwise so I did some digging and I did not know I would find this. This is amazing!!

LikeLike

We are Descendants Of John Basse English immigrant and Elizabeth these are my Great Grandparents! Any information (PICTURES) would be greatly APPRECIATED!

LikeLike

Please join us at Bass Geneology of the New World. I am a direct decendant through grandpa’s! We have lots to share! Email vanleer36@gmail.com and I will send an invite!

LikeLike

Keziah Bass was not “unmarried.” She married William Edward Baldwin (birth 1673 or 1677) and they had at least 2 children, Katherine and Parthenia. Parthenia married Thomas Parsons. Keziah did die young, though, at age 29.

LikeLike

I noticed there wasn’t much mentioned about William (b. 1654) and Catherine (b. 1655) other children – especially John Bass (b. 1673). I’ve been tracing my ancestry back through the Bass family (and the Bassanos – but that’s a whole different beast).

I’d love to connect with anyone else sharing history with John (b. 1673) and Mary (b. 1670), especially if they end up in the NC group!

(My Bass line ends with Mary Ann (b. 1839), ending up in MS for a few generations until my grandparents moved north in the 50s)

LikeLike